What Are the Limitations of Traditional Machining vs Laser Machining for Intricate Features?

Traditional small feature machining falls under several methods and includes techniques from pre-computer technology like lathes, milling, drilling, grinding and others. With the onset of the computer age and advancements not only in technology but the need for a higher degree of quality and consistency amongst manufactured components post 1947, the “traditional” methods now are known as their past names but with CNC or computer numeric control, as a prefix. For over the past 65 years, CNC methods have become the backbone of manufacturing while moving forward alongside with newer technologies like laser technology. During this time, both methods continue to produce complex geometry manufacturing. Traditional machining methods have always had challenges with tool wear, distortion and heat affect. These are overcome by many ways with techniques and processes that are suited for every distinct project. For creating intricate features with fine details and tight tolerances, CNC machining and laser technology both have great capabilities, but also have some limitations which are inherent to the technology being applied. When comparing traditional machining and laser machining for intricate features, it’s essential to understand the distinct limitations each method presents. Here’s a breakdown:

Traditional Machining Limitations:

- Tool Wear and Contact:

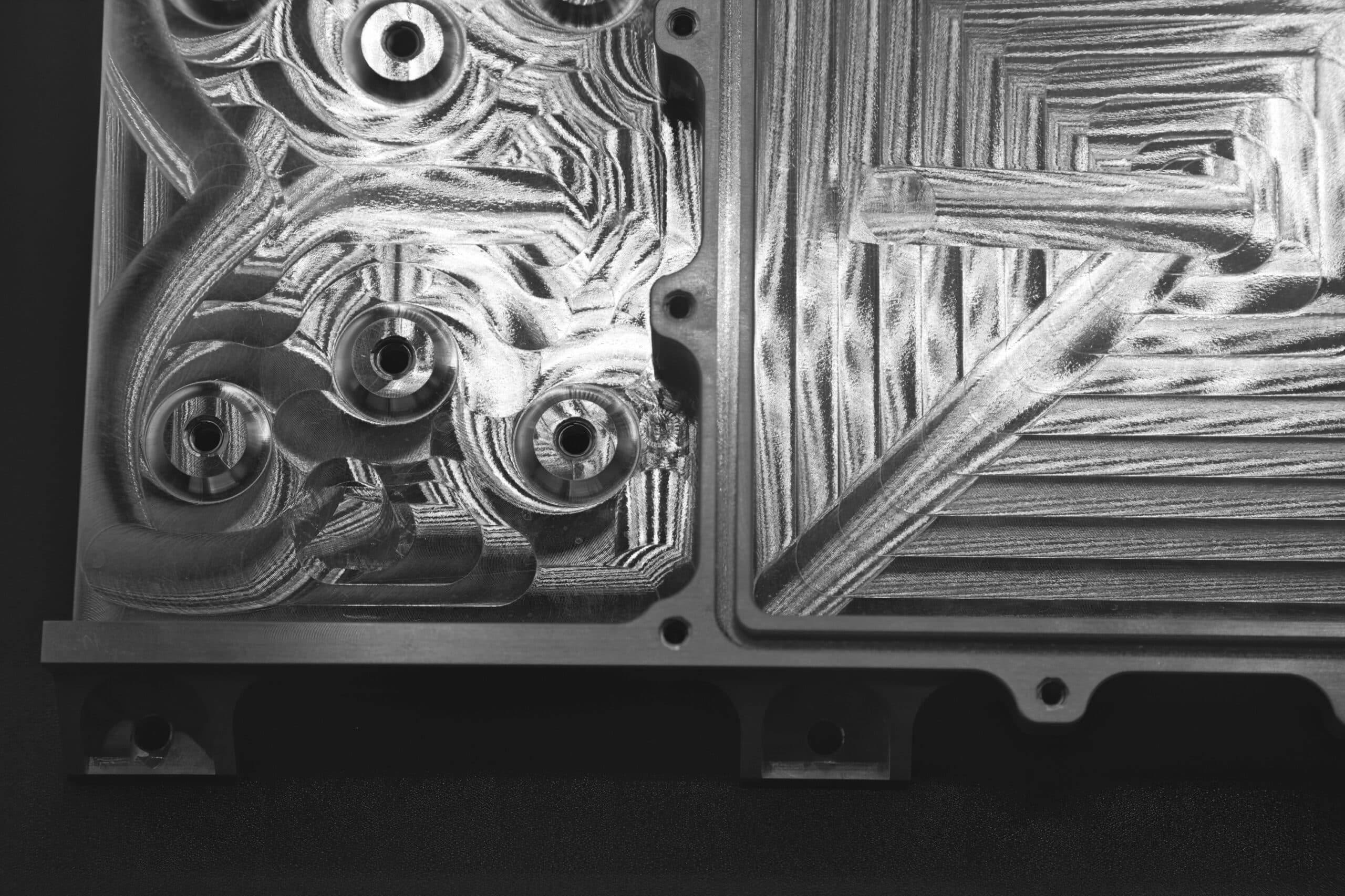

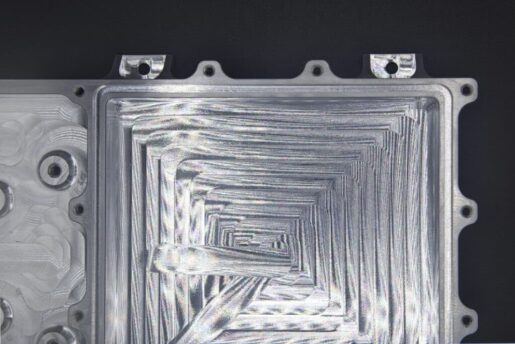

- Traditional methods are a subtractive manufacturing process, relying on physical contact between a cutting tool and the workpiece. The raw material is formed often into complex 3,4 and 5 axis components. This leads to tool wear, requiring frequent replacements and potentially affecting precision over time. The forces involved can also distort delicate workpieces, limiting the ability to create very fine or fragile features.

- Smaller tools can break easily and need slower processing in order to maximize the tool life. Even with small tools, CNC machining involves physical contact, which generates stress during the cutting. Stress can distort or damage delicate workpieces, especially when working with fragile materials or creating very fine features. This is a major issue when working with very small parts, as they are inherently more susceptible to these forces.

- Setup and Time:

- Traditional machining often requires more extensive setup, including tool changes and fixturing, which can increase production time and cost. The process can be slower than laser machining, especially for complex shapes. It has, however, a repeatable process where high production volume can be processed.

- Heat -Affected Zones:

- Traditional machining can still create heat that can affect the material being worked on. Careful planning of the work flow while using coolants are a necessity.

- Material Handling:

- Good for cutting thicker materials in raw form of blocks, plates and rods. Thinner sheets and metal foils tend to be challenging and better done by laser technology or other methods.

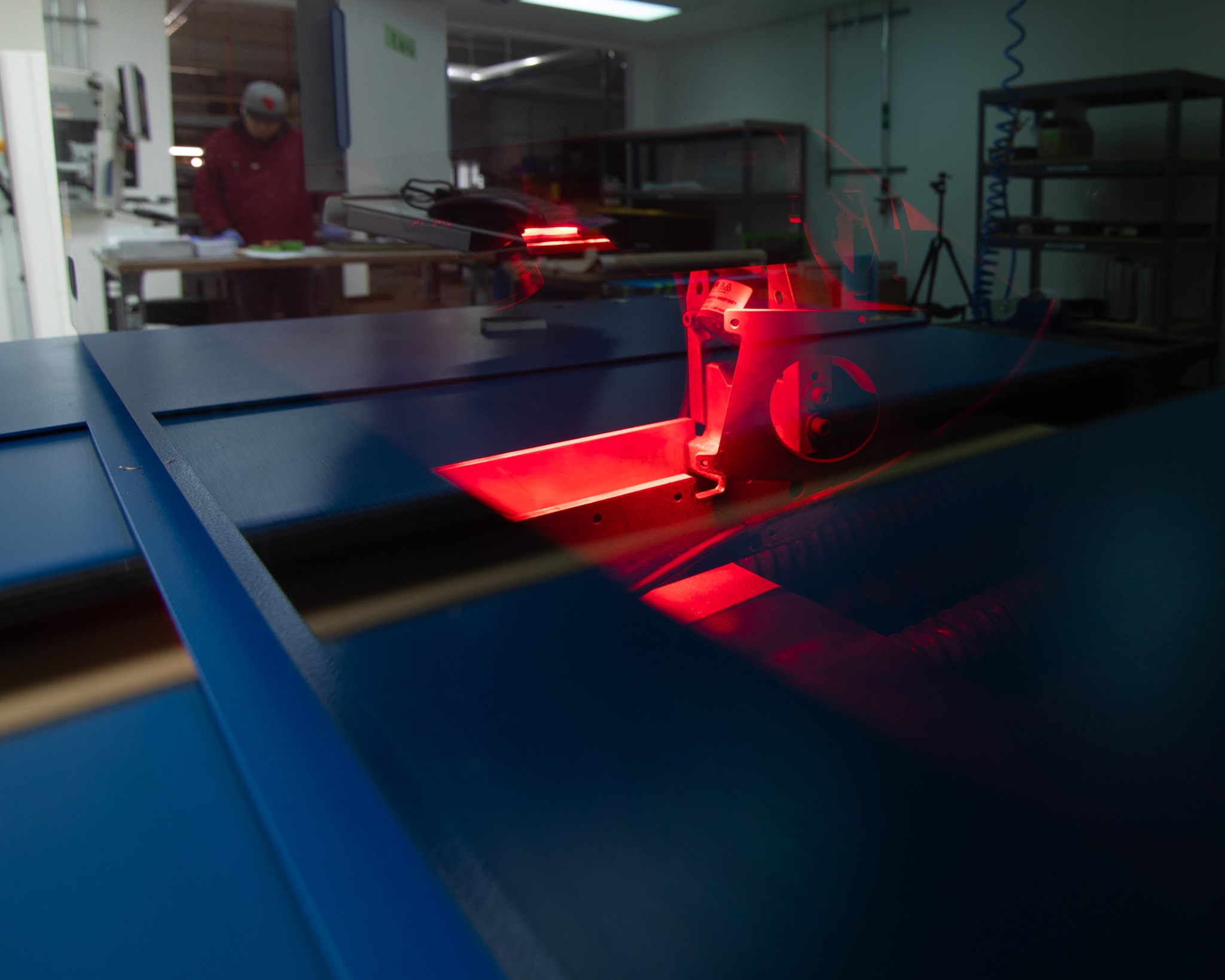

Laser Machining Limitations:

- Material Thickness:

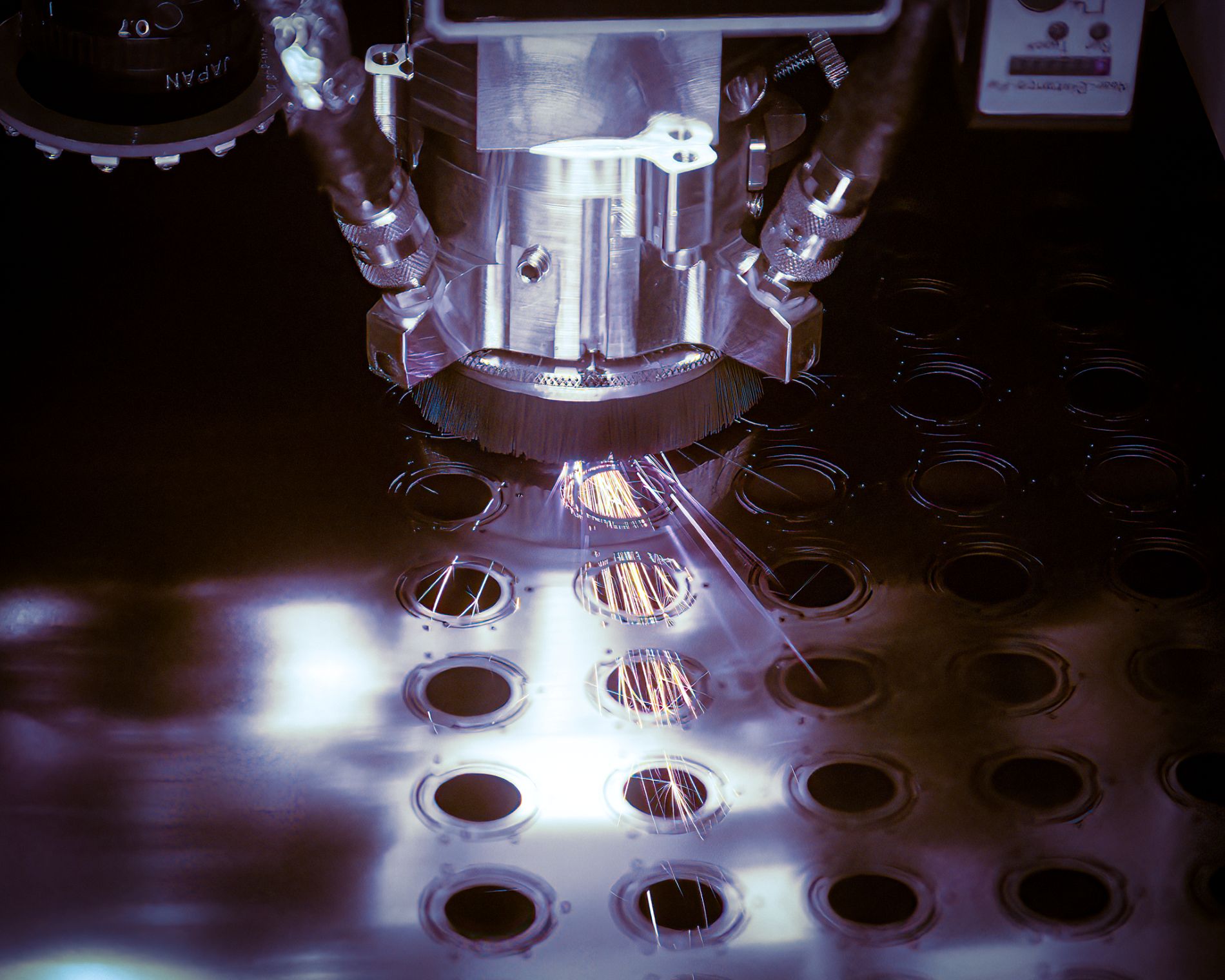

- Laser machining is generally more effective for thinner materials. Cutting very thick materials can be slow and may result in lower quality cuts.

- The beam diameter of a laser is constant and programmed to cut all features, larger and smaller. They can be programmed to cut fine intricate geometry at a slower rate, with more laser passes and adjusting the power or wattage and best at cutting flat 2D components.

- Material Properties:

- Highly reflective materials, such as some metals, can be difficult to process with lasers, as they reflect the laser energy rather than absorbing it. Some materials may produce undesirable fumes or byproducts when laser-cut, so cautionary steps must be taken to review the materials properties, which include chemical make-up, thermal threshold, and hardness.

- Heat-Affected Zone (HAZ):

- While lasers offer precise heat control, they can still create a HAZ depending on the laser systems used and material cut. This can be a concern for sensitive applications.

The mentioned differences are the operational distinctions and general differences between traditional machining methods and laser manufacturing, but there is more in the big picture between these two methods. This does not mean that one is better than the other but does indicate options to come forward for the other process to be complimentary in a manufacturing role, when the current technology has challenges.

The Finer Details

Precision cutting small parts has evolved into fine-detail machining, supporting complex industry requirements from the medical, automotive, nuclear, tele-communications and others. When small feature machining with intricate details is done by CNC methods, there are some limitations compared to laser technology like small holes, slots, slits and similar geometries. Laser systems come in a wide variety of technologies that can overlap on some aspects while offering different manufacturing capabilities. For example, 3,4, or 5um holes are possible and with no heat-affected zones or HAZ with Pico-second and Femto-second lasers. This is far beyond what CNC methods can do. Complex geometry manufacturing is done with laser processing in non-metallic materials where filters and grid arrays are cut. CNC drilling or milling, though accurate, are not meant to process ultra-thin foils and polymers in sub 0.381mm thickness. UV laser drilling for instance, can process materials with an acrylic adhesive backing and paper liner. These cuts can be as small as 75um and “kiss cut” to the liner. Kiss cutting is where the feature is cut to but not through. Because laser technology uses focused beams of light, the cutting tool is smaller than CNC methods, offering design capabilities for sharp corners and radius from 20-25um. For CNC machining, small feature manufacturing would be done with specialized micro-machining tools of about 0.5mm in diameter.

In conclusion, while traditional CNC machining has proven effective for numerous applications, it encounters limitations when it comes to manufacturing some small, intricate features and materials. The precision required for fine geometries, such as holes, slots, and slits, often surpasses the capabilities of CNC technology. Laser systems, however, excel in this area, offering unparalleled precision and versatility. With the ability to cut extremely fine details, such as 3, 4, or 5 micrometer holes, without creating a heat-affected zone, laser technology provides a significant advantage. Additionally, UV laser drilling can achieve remarkably small cuts, down to 75 micrometers, with “kiss cutting” capabilities, highlighting its superiority in processing ultra-thin foils and polymers. Ultimately, while CNC machining remains valuable for many manufacturing tasks, laser technology represents a complementary and often superior solution for producing small, intricate features.